For more than 40 years, Dr. Gottman studied what makes marriages work. I’ve observed thousands of couples, and many of them—the masters—can skill-fully solve their problems.

Yet many others get stuck in their conflicts. Even couples who attend one of my institute’s workshops or therapy sessions have a hard time putting what they learn into practice.

I’ve found that we can help 70 to 75 percent of these couples. But what about the other 20 to 25 percent? How do we help them? What separates them from the masters?

To answer this, I looked at focus groups we did around the United States, involving couples at every social class level and from every ethnic and racial group in the country. I looked at work we did that was funded by the federal Administration of Children and Families, looking in particular at couples about to have a baby. I looked at a large study we did of newlyweds, starting a few months after their wedding. I looked at work we did with the families of soldiers who were deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan.

What I found was that the number one most important issue that came up to these couples was trust and betrayal. I started to see their conflicts like a fan opening up, and every region of the fan was a different area of trust. Can I trust you to be there and listen to me when I’m upset? Can I trust you to choose me over your mother, over your friends? Can I trust you to work for our family? To not take drugs? Can I trust you to not cheat on me and be sexually faithful? Can I trust you to respect me? To help with things in the house? To really be involved with our children?

Trust is one of the most commonly used words in the English language—it’s number 949. When I went to Amazon.com and typed in “trust,” I was surprised that 36,000 books came up. Now, a lot of these were business books, on how to set up a financial trust. But most of them were really about trust in relationships, and trust in general. On Psych-Info, the database that psychologists use to do a literature review, there were 96,000 references to “trust.” And it turns out that when social psychologists ask people in relationships,

“What is the most desirable quality you’re looking for in a partner when you’re dating?”, trustworthiness is number one. It’s not being sexy or attractive. It’s really being able to trust somebody. Through my research, I’ve found that trust is essential to healthy relationships and healthy communities—and I’ve started to learn how we can build trust.

Why trust is important

Trust isn’t just important for couples. It’s also vital to neighbourhoods and states and countries. Trust is central to what makes human communities work.

In a recent line of research on “social capital,” sociologists ask people: “Do you think people can be trusted?”

This research shows there are low- and high-trust regions of the United States. Nevada is a very low-trust region. Minnesota is a very high-trust region. The Deep South is a very low-trust region. We see similar disparities internationally. In Brazil, two percent of people say they trust other people. In Norway, 65 percent say they trust other people.

So what are the characteristics of low-trust regions? Few people vote, parents and schools are less active. There’s less philanthropy in low-trust regions, greater crime of all kinds, lower longevity, worse health, lower academic achievement in schools.

And low-trust areas have greater economic disparities between the very rich and the very poor—and the greater the discrepancy between the very rich and the very poor in a country, the more it predicts economic decline in that country.

Clearly, there are vast implications of low trust for states, for neighbourhoods, for countries. Isn’t it amazing that it’s in the best interests for us to care economically about the people who are disenfranchised in this country? Yet over the last 50 years, CEOs in the U.S., on average, have gone from making 20 times what the average worker makes to 350 times what the average worker makes. Harvard University political scientist Robert Putnam wrote the classic book on social capital, Bowling Alone, which documents the dramatic decline of trust and community in the United States over the last 50 years. Yet when Putnam was asked, “Okay, how do you change all this?”, he had to say, “I don’t really know.”

I think part of the answer involves first defining trust and measuring it scientifically. Science requires us to be precise and objective. When we measure something objectively and precisely, we automatically get a recipe for how to fix it.

The trust metric

So how can we define trust? To find out, I went back to relationships and asked: Can we create a metric of trust and betrayal?

We usually think of betrayal as a big terrible event, like discovering that your partner is having a sexual affair. But it can be more subtle. It can happen in just one interaction.

Let me explain what I mean. In my research, we filmed an interaction between a couple and had each partner turn a rating dial as they watched their tape afterward.

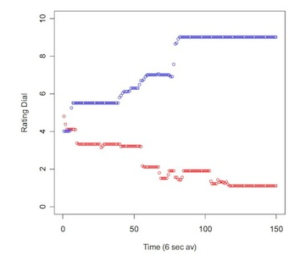

![]() On this graph, you can see how one couple rated their interaction. The blue dots represent the wife’s ratings over 15 minutes of conversation; the red dots represent the husband’s ratings. When you add them together, these ratings are a constant, which means that in this interaction, her gain is his loss and his gain is her loss.

On this graph, you can see how one couple rated their interaction. The blue dots represent the wife’s ratings over 15 minutes of conversation; the red dots represent the husband’s ratings. When you add them together, these ratings are a constant, which means that in this interaction, her gain is his loss and his gain is her loss.

This is what’s called in game theory a “zero-sum game.” You’ve probably all heard of the concept. It’s the idea that in an interaction, there’s a winner and a loser. And by looking at ratings like this, I came to define a “betrayal metric”: It’s the extent to which an interaction is a zero-sum game, where your partner’s gain is your loss.

On the other hand, by trust we really mean, mathematically, that our partner’s behaviour is acting to increase our rating dial. Even though we’re disagreeing, my wife is thinking about my welfare, my best interests.

When we scientifically tested these so-called trust and betrayal metrics, we found that a high trust metric is correlated with very positive outcomes, such as greater stability in the relationship.

In a 20-year longitudinal study of couples in the San Francisco Bay Area that I recently completed with UC Berkeley psychologist Bob Levenson, we found that about 11 percent of couples had a zero-sum game pattern, like in that graph. Every six years, we would re-contact all of the couples in the study, and they would come back to Bob’s lab at Berkeley. Yet we noticed that many of the zero-sum couples weren’t coming back. I thought maybe they dropped out because they found the whole thing so unpleasant. Well, it turns out that they didn’t drop out. They died.

Fifty-eight percent of zero-sum game couples’ husbands died over this 20-year period, whereas among “cooperative-gain” couples, who didn’t have that pattern, only 20 percent of husbands died in that 20-year period. This was true even after controlling for the husband’s age and initial health. Now this is an outcome that’s pretty reliably measured: You can really tell if somebody’s dead or alive.

In a second study, we tried to find out how this could be. And we discovered that if a wife trusts her husband, both of their blood consistently flows slower—not only during their conflict discussion but at other times as well. That’s associated with better health and a longer life. So maybe that’s the mechanism through which men with a high “betrayal metric” are dying. But why are the men dying and not the women?

It turns out that trust is related to the secretion of oxytocin, which is the “cuddle hormone,” the hormone of bonding. It’s also a hormone we secrete when we have an orgasm; the stronger the orgasm, the more oxytocin we secrete.

Interestingly enough, men don’t just secrete oxytocin after an orgasm; they secrete vasopressin as well. Vasopressin is a hormone associated with aggression. After a male rat has had an orgasm with a female rat, he not only is enjoying the experience, he’s also trying to ward off rivals.

So there is evidence that the bonding experience of having an orgasm with somebody—secreting oxytocin, that trust hormone—is very powerful, it suspends fear. But it doesn’t have as protective an effect in men as it does in women.

Building trust

But how do you build trust? What I’ve found through research is that trust is built in very small moments, which I call “sliding door” moments, after the movie Sliding Doors. In any interaction, there is a possibility of connecting with your partner or turning away from your partner.

Let me give you an example of that from my own relationship. One night, I really wanted to finish a mystery novel. I thought I knew who the killer was, but I was anxious to find out. At one point in the night, I put the novel on my bedside and walked into the bathroom.

As I passed the mirror, I saw my wife’s face in the reflection, and she looked sad, brushing her hair. There was a sliding door moment.

I had a choice. I could sneak out of the bathroom and think, “I don’t want to deal with her sadness tonight, I want to read my novel.” But instead, because I’m a sensitive researcher of relationships, I decided to go into the bathroom. I took the brush from her hair and asked, “What’s the matter, baby?” And she told me why she was sad.

Now, at that moment, I was building trust; I was there for her. I was connecting with her rather than choosing to think only about what I wanted. These are the moments, we’ve discovered, that build trust.

One such moment is not that important, but if you’re always choosing to turn away, then trust erodes in a relationship—very gradually, very slowly.

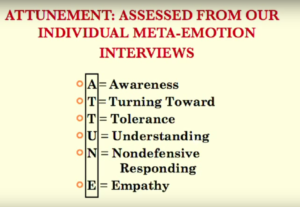

My graduate student Dan Yoshimoto has discovered that the basis for building trust is really the idea of attunement. He has broken this down with the acronym ATTUNE, which stands for:

Awareness of your partner’s emotion;

Turning toward the emotion;

Tolerance of two different viewpoints;

trying to Understand your partner;

Non-defensive responses to your partner;

and responding with Empathy.

By contrast, the atom of betrayal is not just turning away—not just turning away from my wife’s sadness in that moment—but doing what Caryl Rusbult called a “CL-ALT,” which stands for “comparison level for alternatives.”

What that means is I not only turn away from her sadness, but I think to myself, “I can do better. Who needs this crap? I’m always dealing with her negativity. I can do better.”Once you start thinking that you can do better, then you begin a cascade of not committing to the relationship; of trashing your partner instead of cherishing your partner; of building resentment rather than gratitude; of lowering your investment in the relationship; of not sacrificing for the relationship; and of escalating conflicts.

I believe that by understanding the dynamics of trust and betrayal, we can work to make relationships more trusting. But more than that, we can help people become more trustworthy.

By John Gottman – The nation’s top marriage expert explains why trust is essential to couples and communities–and how we can build it.

Leave A Comment